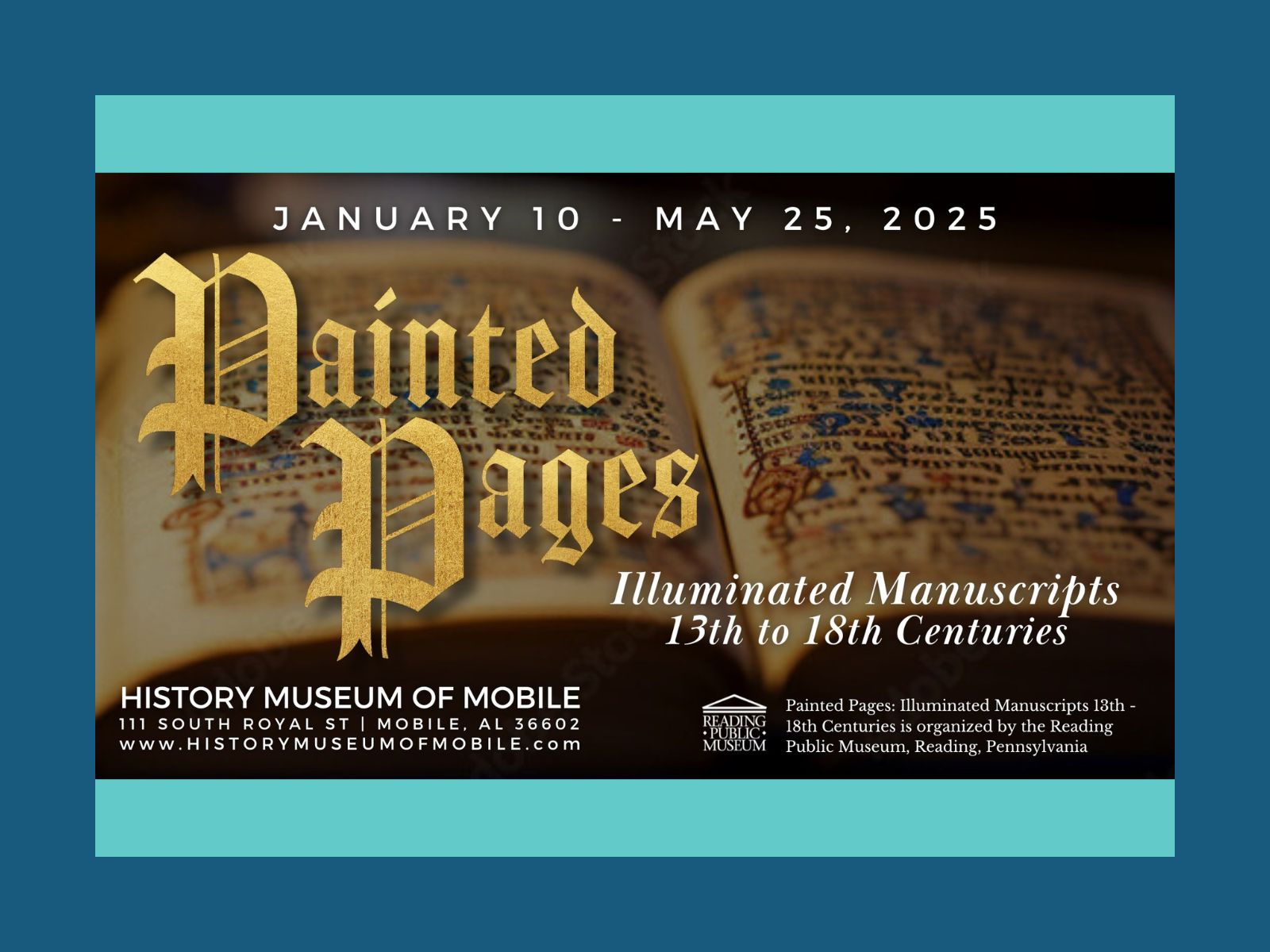

HISTORY MUSEUM OF MOBILE TO HOST ILLUMINATED MANUSCRIPTS EXHIBITION

MOBILE, Ala. – THE HISTORY MUSEUM OF MOBILE is excited to announce the next major exhibition, Painted Pages: Illuminated Manuscripts, 13th – 18th Centuries, opening January 10, 2025. This engaging exhibition includes more than thirty-five works—some with elaborate gold leaf decoration and intricate ornament— from medieval Bibles, Prayer Books, Psalters, Books of Hours, Choir Books, Missals, Breviaries, and Lectionaries drawn from the collection of the Reading Public Museum in Reading, Pennsylvania, who organized the exhibition. Examples of the materials—parchment, vellum, gold leaf, and minerals which were ground into pigments—used by artists before the age of printed books to create these extraordinary pages are also featured in the exhibit. The exhibition opens on January 10, 2025 and will be on view through May 25, 2025, sponsored locally by the Hearin-Chandler Foundation and WKRG TV-5.

Highlights include a lavish Bifolio from a Book of Hours with illuminations by Joachinus de Gigantibus de Rotenberg (German, active 1440s – 1490s), a Perugian Leaf from a Dominican Missal from the late fourteenth century, a large Bifolio of a Spanish Choir Book from the fifteenth century, a Hebrew scroll of the Book of Esther from the eighteenth century, and a leather-bound Italian Gradual containing the chants for the mass penned in the 1720s.

Most of the works date from the thirteenth through the eighteenth centuries and are created with ink on parchment or vellum (animal skin). French, Italian, Spanish, Dutch, Flemish, English, and German examples will be included in the exhibition. Additionally, non-Western sheets, including a sumptuous seventeenth-century leaf from the Koran and Shahnameh (the illustrated Persian Book of Kings) pages from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Nearly all of the sheets came to the Reading Public Museum through Otto Ege, a well-known Cleveland-area bookseller and specialist who was born in Reading, Pennsylvania.

“This exhibition is a fascinating view of the history of the book and book art. Illuminated manuscripts are some of the best-preserved objects from this timeframe and offer a unique lens for visitors to understand just how diverse book art can be,” said Jon Sexton, Director of the History Museum of Mobile. “Visitors will see how much time and effort were exerted to bring the activities, interests, and values of the artists’ world to life and come to understand, even outside religious use, why so many wealthy patrons were drawn to having these works produced.”

A series of programs will enrich the visitor experience and enhance the educational value of the exhibition. The planned programming is designed to support meaningful connections to exhibition themes and will include special workshops for children and adults.

The History Museum of Mobile is open Monday – Saturday from 9:00 AM – 5:00 PM and Sunday from 1:00 PM – 5:00 PM. Admission is free on the first Sunday of each month.

ABOUT ILLUMINATED MANUSCRIPTS: Handwritten books, or manuscripts, existed for more than one thousand years before Gutenberg printed his first Bible. The word manuscript is taken from the Latin manu scriptus, meaning written by hand. Illumination is the art of decorating handwritten books with gold, silver, and colored inks and paints to embellish pictures, letters, and margins. A single manuscript created in this way would have taken months or even years to complete, making them extremely costly to produce. Surviving manuscripts, all executed using similar techniques, have been found in Europe, the Middle East, Asia, and Mesoamerica. Many of these provide us with the only surviving examples of early painting. This exhibition focuses on the rich tradition of manuscript illumination in Europe as well as the Middle East.

In the early Middle Ages, most books were produced in monasteries for religious use. Illumination was reserved for special books, such as altar Bibles used in cathedrals, as well as books commissioned by rulers for their personal use or as diplomatic gifts. Smaller religious books like psalters and books of hours were produced for the wealthy as signs of status. By the beginning of the thirteenth century, with the growth of universities in Europe, the demand for secular books increased as did the production of illuminated manuscripts. By the late fourteenth century, commercial scriptoria (writing centers) grew up in the large cities of Europe and the Middle East where more affordable manuscripts were duplicated by scribes or students. Many were personalized with heraldry, portraits, and illustrations specified by the buyers who commissioned them. By the end of the period, many of the painters were women, especially in Paris.

Although paper was available in southern Europe as early as the twelfth century, its use did not become widespread until the late Middle Ages. Typically, vellum or parchment, made from stretched, treated animal skins, were used for manuscript leaves. A large manuscript book might require the skins from a whole herd of cows or sheep. A scribe would first write out the text using an ink-pot and a sharpened quill or reed pen. Script styles evolved over time and the origin of a manuscript can often be identified by the book hand or script used. Once the text was filled in by the scribe, the manuscript was turned over to the illuminator for decoration and illustration. The pigments which literally “illuminated” the books were made from a variety of substances: animal, vegetable, and mineral. The use of gold signified luxury, wealth, and status. Ultimately, the introduction and widespread use of the printing press led to the decline of hand-written manuscripts.

Stay Connected

Fill out and submit the form below to get regular updates from Mobile Chamber delivered directly to your inbox.